How to make agents understand the environment descriptions and act accordingly?

[Spoiler Alert] Language-conditioned world model improves policy generalization by reading environmental descriptions

PDF version

Abstract

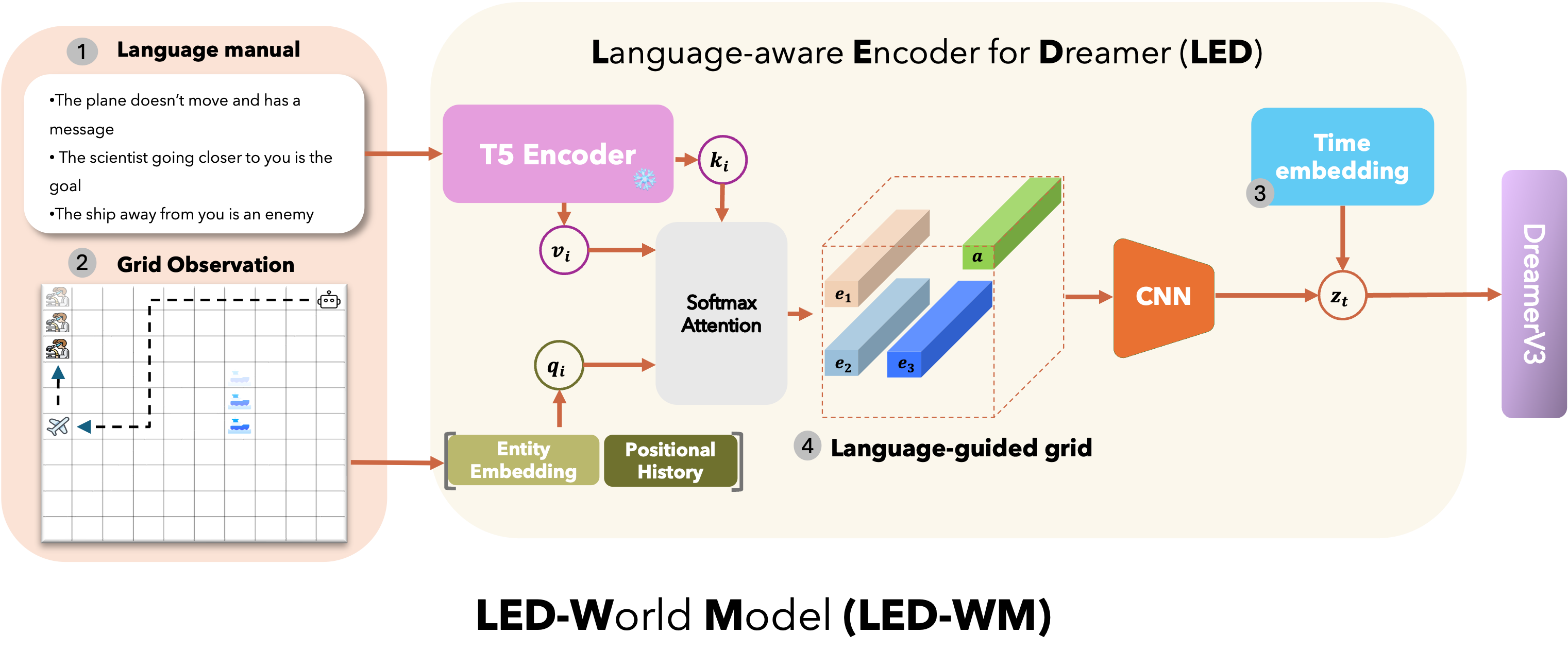

To interact effectively with humans in the real world, it is important for agents to understand language that describes the dynamics of the environment—that is, how the environment behaves—rather than just task instructions specifying what to do. For example, a cargo-handling robot might receive a statement like “the floor is slippery so pushing any object on the floor will make it slide faster than usual”. Understanding this dynamics-descriptive language1 is important for human-agent interaction and agent behavior. Recent work [DynaLang et al., LWM et al., Reader et al.] address this problem using a model-based approach: language is incorporated into a world model, which is then used to learn a behavior policy. However, these existing methods either do not demonstrate policy generalization to unseen games or rely on limiting assumptions. For instance, assuming that the latency induced by inference-time planning is tolerable for the target task or expert demonstrations are available. Expanding on this line of research, we focus on improving policy generalization from a language-conditioned world model while dropping these assumptions. We propose a model-based reinforcement learning approach, where a language-conditioned world model is trained through interaction with the environment, and a policy is learned from this model—without planning or expert demonstrations. Our method proposes Language-aware Encoder for Dreamer World Model (LED-WM) built on top of DreamerV3 [Hafner et al.]. LED-WM features an observation encoder that uses an attention mechanism to explicitly ground language descriptions to entities in the observation. We show that policies trained with LED-WM generalize more effectively to unseen games described by novel dynamics and language compared to other baselines in several settings in two environments: MESSENGER and MESSENGER-WM. To highlight how the policy can leverage the trained world model before real-world deployment, we demonstrate the policy can be improved through fine-tuning on synthetic test trajectories generated by the world model.

1 We will call dynamics-descriptive and environment-descriptive language interchangeably.

Problem Formulation

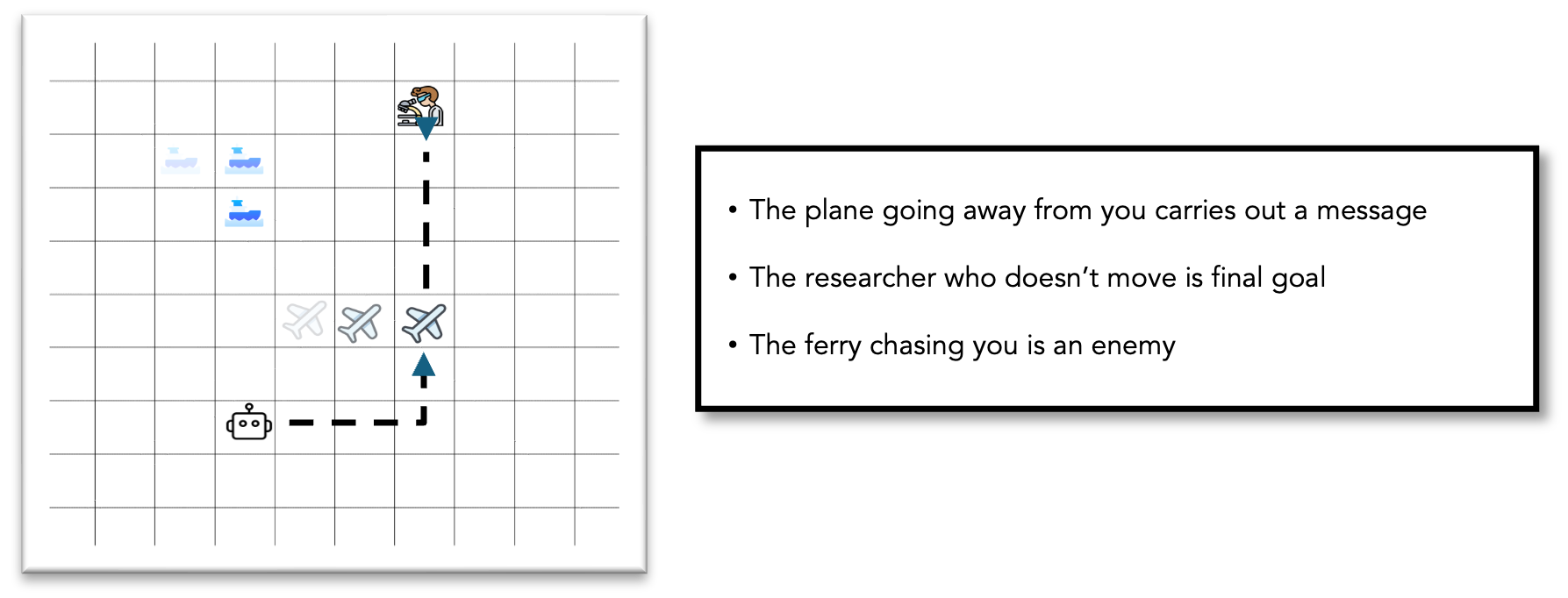

Figure 1: An example of environment-descriptive language in a game play. The observation includes a 10 × 10 grid-world with three entities represented by their associated symbols: (ferry - 🚢), (plane - ✈️), (researcher - 👨🔬) and one agent (depicted by 🤖). The observation also has a manual in the right, which describes the dynamics of the game. The agent can navigate the grid using five actions: left, right, up, down, and stay. The agent can only interact with entities when it is in the same grid cell as the entity. The agent’s task is to identify roles of all entities from the manual, go to the messenger, then go to the goal, while avoiding the enemy. Shaded icons indicate one possible scenario of entity movement over time. By observing entity movement patterns and grounding language to entities based on their behaviors, the agent can infer the roles assigned to each entity: (ferry-enemy), (plane-messenger), and (researcher-goal). The agent can then execute an appropriate plan to complete the task. The dashed line in the grid shows such a possible plan.

Method

Figure 2: Overview of our proposed world model LED-WM. The world model input consists of: ① a language manual L, ② a grid-world observation representing entity and agent symbols, and ③ the current time step t. Entity, agent symbols, and time step are encoded using learned embeddings, while L is encoded via a frozen T5 encoder. To represent each entity, we employ a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) that processes the entity embedding and its temporal information, capturing its movement pattern relative to the agent, to produce a query vector. We apply an attention network between the query vectors and the sentence embeddings to align each entity with its corresponding sentence. The resulting vectors are then put into their respective entity positions. This produces ④ a language-grounded grid G_l, which is then processed by a CNN. The extracted feature vector is flattened and concatenated with the time embedding to form final observation representation x_t.